ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE, PROMISE OR PERIL: PART 2 – REGULATING AI

by Dr. James Baty PhD, Operating Partner & EIR and Tarek El-Sawy PhD MD, Venture Partner

RAIVEN CAPITAL

This is our second release in our series on governing

Artificial Intelligence – AI Promise or Peril

This release consists of two sections

AI Regulatory Challenges & Models

AI Regulation Examples & Issues

The third release will cover AI from a VC perspective. The first release on AI Ethics is available here.

In the inaugural episode of our ‘AI, Promise or Peril’ series, we delved into the clamor surrounding Artificial Intelligence (AI) ethics—a field as polarizing as it is fascinating. Remember the Future of Life Institute’s six-month moratorium plea, backed by AI luminaries? Opinions ranged from apocalyptic warnings to messianic proclamations to cries of sheer hype.

We observed that the answer to AI governance isn’t a one-size-fits-all solution; rather, it’s a cocktail of corporate self-governance, industry standards, market forces, and international legislation—sometimes with AI policing itself. Our journey began with the first episode dissecting the growing landscape of AI ethics frameworks, concluding that the quest for the perfect blend of public, private, and governmental guidelines is only just beginning.

In today’s installment, let’s attempt an overview of formal AI regulation, including challenges in regulating AI, primary regulatory models, key regulation implementation, and outstanding issues.

No single guide to AI governance can cover everything. Our goal is a meta-guide that highlights the key issues, actors and approaches, with an idea to be informed enough to evaluate how AI impacts the VC ecosystem.

AI REGULATORY CHALLENGES AND MODELS

Why AI Regulation is a Must

Regulating tech isn’t new; we’ve done it for radio, TV, cars, planes, medical devices, and the Internet. These regulations address safety, fairness, and privacy, often leading to new laws or even regulatory bodies.

But AI is also a different beast. It not only introduces fresh risks, but also amplifies existing ones. Consider self-driving cars: should they not be regulated for safety like traditional cars? What if they’re also collecting and selling your travel data, leaking your financial information, or denying you access based on biased facial recognition errors? Who’s responsible if your self-driving autonomous vehicle kills someone? Which ‘agent’ does the regulation focus on for liability? Manufacturer, AI navigation software developer, GPS service, passenger/owner, everyone?

Notably, AI isn’t always easily scrutinized; it’s more so embedded in code rather than distinct physical objects. This makes oversight more challenging, yet urgently needed. Case in point: research by Joy Buolamwini and Timnit Gebru showed commercial gender classification systems had error rates of up to 34.7% when identifying darker-skinned females. The frightening outcome – such errors have already led to wrongful arrests. And, oh yeah, Amazon’s facial recognition tech falsely identified 28 black members of the US Congress as criminals. No surprise that the EU AI Act now classifies public facial recognition as ‘unacceptable risk’ – prohibited.

Regulating AI is complex and has wide-ranging implications, from policing, to medicine, to military applications. Two key issues stand out in the imperative: AI brings unprecedented challenges and risks. Similar to regulation of social media, we’re already behind the curve.

While one article can’t cover all the intricacies of AI regulation, understanding the big picture is crucial for business and investment decision-making.

Challenges in Regulating AI

“It takes all the running you can do, to keep in the same place.” — The Red Queen to Alice

AI isn’t just another tech innovation; it’s a whirlwind of unique challenges. Before diving into AI regulation models, let’s highlight the issues making AI a tough nut to crack.

While tech’s pace has always been brisk, AI is exploding. We’ve seen AI underpin tools like Google Search for ages. Yet, within six months of release in 2022, OpenAI’s Chat GPT spurred an all-out arms race: Microsoft threw $13 billion into OpenAI and integrated ChatGPT into Bing and Edge, Google unveiled Bard with DeepMind LaMDA tech, and Facebook shifted gears from Meta to launch open-source LLM tools. Amidst this, Marc Andreesen laments this may be the end of traditional ‘Internet Search’.

The well-known ’Red Queen Problem’ – needing to constantly innovate to keep up — of extreme dynamics makes AI regulation especially challenging, due to several factors:

- Rapid Changes: AI evolves so fast that regulations risk becoming obsolete as soon as they’re enacted.

- Data Drift: Fluctuating data patterns can unpredictably alter AI systems, muddying fairness or accuracy enforcement.

- Market Dynamics: The race for AI dominance could make companies overlook regulatory speed limits, risking non-compliance or loss of edge.

- Security Mutation: Evolving cyber threats necessitate continually updated security standards.

- Resource Utilization: Rapid advancements could make previous resource guidelines irrelevant,

- Ethical Fluidity: Social norms shift, meaning regulations on AI ethics, like bias and discrimination, need constant recalibration.

Though many tech innovations face such hurdles, AI’s dynamic nature is extreme. But remember, this speed of change is only challenge number one in the long list of AI regulatory puzzles. Consider these other significant issues that complicate regulation:

Disruptive Business Models: Emerging technologies like AI blur traditional business and regulatory boundaries, potentially rendering existing frameworks outdated or irrelevant.

Complexity and Interdisciplinary Nature: Navigating the labyrinthine intricacies of AI demands not only specialized technical know-how but also a multifaceted understanding of ethical, social, and economic ramifications.

Jurisdiction and Governance: The borderless nature of tech giants collides with fragmented oversight, complicating governance across sectors like healthcare, finance, and transportation.

Ethical and Social Challenges: Balancing unbiased AI, privacy preservation, and safety protocols in burgeoning technologies is akin to walking a high wire.

Economic Impacts: The tightrope act between regulation and innovation introduces risks—from stifling global competitiveness to perpetuating access inequities in marginalized communities.

Unintended Consequences: The specter of regulatory capture and the paradox of too much or too little oversight pose dual threats to innovation and ethical conduct.

This is not an exhaustive list, but clearly AI regulation poses not just technical risks, but also unique regulatory challenges. These challenges demand a nimble, multi-disciplinary approach that can adapt as technology evolves. Regulatory sandboxes, public-private partnerships, and multi-stakeholder governance models are among the strategies being explored to regulate AI more effectively. Let’s look at the high-level regulatory models available for this daunting task.

Different Models of AI Regulation

Artificial Intelligence regulation is a subject of increasing interest and urgency as AI technologies become more pervasive and impactful. Several models of regulation emerge that aim to ensure the safe and ethical deployment of AI. Here’s a look at the applicability of three commonly discussed regulatory models: the Risk Model, the Process Model, and the Outcomes Model. Each may be more appropriate for different types of AI Applications, market settings, or regulatory goals. They are often combined.

RISK MODEL

The Risk Model of AI regulation focuses on categorizing and assessing the potential risks and dangers associated with specific types of AI technologies or applications. Regulation is tailored according to the level of risk, with higher-risk technologies receiving more stringent oversight.

- Example Application – Autonomous Vehicles: Regulators could classify self-driving cars as high-risk due to potential accidents or injuries. Before reaching public roads, these vehicles might need to pass diverse safety tests under various driving conditions. Additionally, manufacturers could be mandated to maintain significant insurance policies for potential liabilities.

- Key Features:

- Risk Assessment: Prioritize AI technologies based on potential harm to individuals and society.

- Tailored Regulation: Apply differing levels of scrutiny, approval, and monitoring based on risk assessment.

- Compliance Checks: Regular audits or evaluations to ensure risk mitigation.

- Key Implementation: EU Artificial Intelligence Act

PROCESS MODEL

The Process Model focuses on the development, deployment, and operational stages of AI systems. Instead of primarily targeting the technology itself, this model aims to regulate the methods and processes by which AI is created and used.

- Example Application: Facial Recognition: If a company intends to deploy facial recognition in airports, they’d need to align with specific regulatory standards. This would involve using unbiased training data, ensuring algorithm transparency, and instituting human oversight mechanisms. Regular compliance audits might be necessary to verify adherence.

- Key Features:

- Development Guidelines: Setting standards for data collection, training, and algorithm design.

- Transparency: Requirements for disclosing algorithms, data sources, and decision-making processes.

- Operational Protocols: Rules for how AI systems are deployed, monitored, and maintained.

- Key Implementation: NIST AI-Risk Management Framework

OUTCOMES MODEL

The Outcomes Model focuses on the societal and individual impacts of AI, rather than on the technology or the process by which it was developed. This model aims to enforce accountability based on the actual outcomes or consequences of using AI.

- Example Application – AI in Healthcare Diagnostics: For AI systems diagnosing diseases via medical imaging, the emphasis might be on post-deployment outcomes. Regulators would scrutinize the diagnostic accuracy, false positive/negative rates, and any detectable biases. Inconsistencies or significant errors could lead to regulatory penalties or restrictions.

- Key Features:

- Impact Assessment: Evaluation of AI’s societal and ethical implications, post-deployment.

- Accountability: Assigning responsibility for negative outcomes and enforcing penalties.

- Adaptive Regulation: Regulation evolves based on observed impacts, with feedback loops for continuous improvement.

- Key Implementation: US Algorithmic Accountability Act of 2022

Comparing the Risk, Process, & Outcomes models

In these examples, the key takeaway is how the focus of regulation differs:

Risk Model:

- Focus: Focuses on potential hazards before they occur, often requiring preemptive safety measures

- Execution: Strong in pre-market evaluation but can be rigid with predefined risk categories; accountability largely rests with regulators.

Process Model:

- Focus: Focuses on the methods and processes involved in the development and deployment of the technology, often requiring documentation and transparency.

- Execution: Operates both pre- and post-market, adapting to best practices; emphasizes corporate adherence to these practices.

Outcomes Model:

- Focus: Focuses on what actually happens once the technology is deployed, holding parties accountable for negative impacts and possibly requiring corrective action.

- Execution: Typically, post-market, driven by real-world data, and holds entities responsible for those outcomes.

Jurisdictions often mix and match these models based on their unique regulatory needs and philosophies. While each model has pros and cons, hybrids are common to capitalize on multiple strengths. Case in point: the EU AI Act is famed for its Risk Model foundation but also integrates elements from the Process and Outcomes models.

AI REGULATORY EXAMPLES AND ISSUES

Why AI Regulation is a Must

Standardized AI regulation, though advancing, remains a complex terrain. It is clear the inherent risks merit global action. For a sense of the complexity, check out the OECD repository summarizing over 800 AI policy initiatives from 69 countries. The newly-passed EU AI Act and ongoing UN talks are hopeful signs of emerging alignment. Yet, global AI regulatory philosophies aren’t in sync, as Matthias Spielkamp of Algorithm Watch characterized the key players “The EU is highly precautionary” “The United States… has so far been the most hands-off,” and China “tries to balance innovation with retaining its tight control over corporations and free speech…And everyone is trying to work out to what degree regulation is needed specifically for AI.”

Given the transborder issues of business complexity and technical risks, both innovation and regulation would likely benefit from more standardization. Like regulation, this is likely to be a hybrid strategy. Daniel J. Gervais has proposed a model for global agreement, an international framework of ethical AI programming obligations on companies, programmers and users that are then translated locally into compatible regulation. The focus of this alignment would be on three organizations: large bodies of regional collaboration such as the US, EU and OECD (the fastest route to alignment); the WTO and lastly, the UN, for longer term agreements.

Social media’s global reach has made it abundantly clear: tech regulation is a global game—risks don’t respect borders. Now, companies once tempted to jurisdiction shop are finding that unified rules might be less of a headache. And the experts are realizing the risk of AI magnifying technology risks doesn’t stop at the border. Imagine scams like the ‘Business Email Compromise’, or the ol’ ‘Grandparent Scam’, supercharged by deep-fake AI calling from overseas: “Mom! Quick run to the Apple Store and buy some gift cards to get me out of this foreign jail!!” It’s clear: global AI threats need global solutions.

So, let’s consider the key emerging examples of AI regulation – the broad EU AI Act approach, the US Framework and Agency approach, and some major issues.

The EU AI Act – a Risk Based / Omnibus Approach

Similar in approach to Europe’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), the toughest privacy and security law in the world, the region has taken a significant step by passing the EU Artificial Intelligence Act (AIA). The first comprehensive omnibus regulatory framework, and as such (like GDPR), is a global template for AI regulation. Both the GDPR and the AI Act have their legal basis in Article 16 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU), which allows EU institutions to make rules about protecting personal data – although the AIA goes much farther than just personal data. On June 23rd, the European Parliament approved the proposed act, which is now undergoing implementation negotiations with the EU Council and European Parliament.

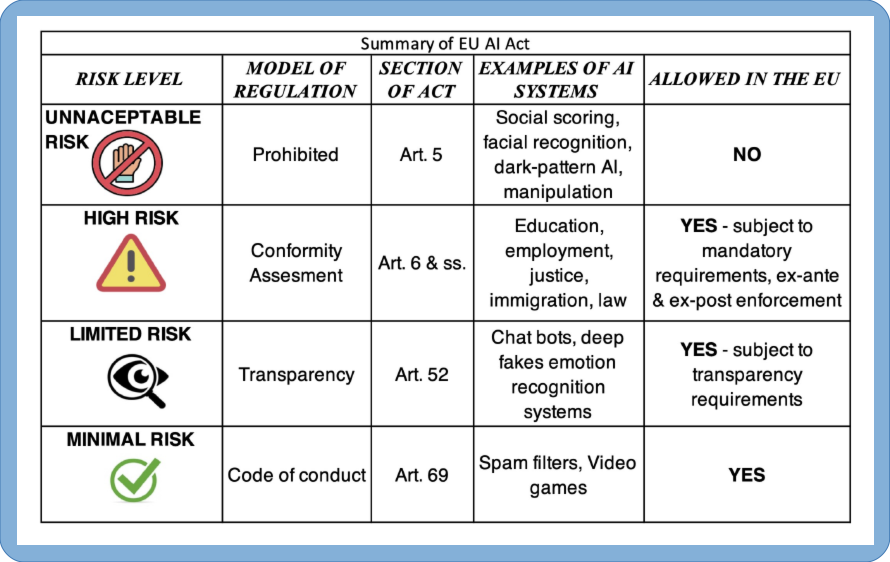

The Act proposes a risk-based governance scheme creating new requirements across a broad range of entities and jurisdictions. This act categorizes AI into four groups: low-risk, minimal-risk, high-risk, and prohibited. High-risk AI applications are those that pose a substantial threat to people’s health, safety, fundamental rights, or the environment. The act also introduces transparency requirements for AI systems. For instance, generative language models like ChatGPT would need to disclose their AI-generated content, differentiate deepfake images from real ones, and incorporate safeguards against the creation of illegal content.

The EU AI Act – The Risk Model Detailed

The regulatory framework defines four levels of risk in AI:

The Act goes hard on ‘Unacceptable Risk’ AI, banning systems that pose clear threats to safety and rights:

- “Dark-pattern AI” that exploits human vulnerabilities for harm.

- “Social scoring” used by authorities to rank trustworthiness.

- Real-time facial recognition in public spaces by law enforcement.

High risk systems are highly regulated and come in two categories

- Embedded AI in already-regulated products (see Annex II).

- Stand-alone systems in critical areas like robotic surgery (Annex III).

These systems will be subject to strict obligations before they can be put on the market, e.g., risk mitigation, ensured high quality data, logging of activity, and appropriate human oversight. This enforces the principles of traceability and accountability we talked about in the ethics article.

It is worth noting that many of the applications described under the Act, such as high-risk applications of AI in aviation, cars, boats, elevators, medical devices, industrial machinery, etc., are already subject to existing agency regulations — such as the EU Aviation Safety Agency.

The EU AI Act – Impact Beyond the EU

The Act doesn’t skimp on penalties. Get caught in a breach of the prohibited AI practices or failure to put in place a compliant data governance program for high-risk AI systems? You’re looking at fines up to €30 million or 6% of your global annual revenue, whichever stings more. That’s notably heftier than GDPR’s max hit of €20 million or 4%. And heads up, global businesses: just like GDPR, with its extraterritorial implications and Adequacy Decision, the AI Act’s reach isn’t limited to the EU. If you’re an outside company aiming to do business in the EU, get ready to play by their AI rules. Expect this Act to shake things up worldwide.

The US – Slow to Pass Omnibus Regulatory Charters

Looking to craft a U.S. AI regulatory masterplan? Take a leaf out of the ill-fated American Data Privacy and Protection Act. Aimed to be the U.S. twin to the EU’s GDPR, it cruised through committee, but got ghosted by the 2022 Congress. The act would’ve had algorithm peddlers run checks before launching inter-stat, plus, annual deep-dives for the big data sharks. Spoiler: comprehensive data privacy or AI regs in the U.S. are still in the vaporware stage.

Meanwhile, states don’t wait for the Feds to catch up. California hit fast-forward with its Consumer Privacy Act post-GDPR. And now in the AI arena, you’ve got states from Cali to Texas to New York cooking up their own rulebooks. San Francisco? They went all in, giving facial recognition tech the boot for local government. Still there is hope for a consistent US-wide AI regulatory framework, before a hodgepodge of state and city laws gets too fractured to follow.

The US approach – Strategy More Focused on Process Models

In the U.S., efforts are in high gear on several fronts to develop a broad regulatory framework for AI, similar to the work done in the EU. At a strategic policy level, the National Security Commission on Artificial Intelligence was established in 2018 to examine AI, machine learning, and related technologies in national security and defense. There is also encouraging work between the US and the EU to align the elements of their respective AI regulatory frameworks.

Two key policy documents have emerged in the US AI regulation strategy. In 2022, the White House’s Office of Science and Technology Policy issued the Blueprint for an AI Bill of Rights, outlining core principles for the responsible AI design and deployment. The show-stealer is NIST’s AI Risk Management Framework from 2023. Notably, NIST’s framework mirrors the EU AI Act’s risk-centric stance, but is distinguished by its life-cycle methodology to identify assess and monitor emerging AI risks. The NIST Model extends the 2022 OECD Framework for the Classification of AI systems, with modifications elaborating critical processes of test, evaluation, verification, and validation (TEVV) throughout an AI lifecycle.

The AI RMF Core is composed of four functions: GOVERN, MAP, MEASURE, and MANAGE. Each function is broken down into categories and sub-categories each with specific actions and outcomes. While it may be a while before the use of the NIST model is required by regulations to be applied to general commerce, this model already being adapted in US government procurement policies related to AI technology.

The US Approach – Regulatory Agency-Centric Implementation

But the lack of a federally mandated omnibus AI regulatory framework, doesn’t mean the US Federal government isn’t already regulating AI. significant AI regulations are being enacted by various US government agencies. While waiting for comprehensive AI regulation, agencies such as the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the Department of Commerce (DOC), Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) , and the Government Accountability Office (GAO) have taken specific steps to regulate AI. The FTC, for instance, has announced it is focusing on preventing false or unsubstantiated claims about AI-powered products. And in April 2023, the FTC, the Civil Rights Division of the US Department of Justice, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, and the US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission issued a joint statement committing to fairness, equality, and justice in emerging automated systems, including those marketed as “artificial intelligence” or “AI”.

The FDA has also been involved in regulating AI in the medical field. In 2019, they published a discussion paper on Artificial Intelligence/Machine Learning (AI/ML)-based software as a medical device, followed by public meetings and workshops on specific medical uses, patient trust, and device safety and effectiveness. The FDA issued a finalized AI/ML action plan in January 2021, and as of October 2022, FDA has authorized over 500 AI/ML-enabled medical devices via the 510(k), De Novo, and Premarket Approval (PMA) procedural pathways.

US – FDA / Medical AI Deep Dive

Let’s dial back on the strategic excitement, and focus on a specific sector: medicine. In April 2023, the FDA set forth a strategic direction for the rapidly evolving landscape of AI and Machine Learning (AI/ML) within healthcare. The Agency released draft guidance proposing an approach to ensure the safe and rapid modification of AI and machine learning-enabled devices in response to new data. This guidance underscores a balanced approach, facilitating continuous improvements in machine learning-enabled device software functions, while prioritizing patient safety and effectiveness.

Anyone who has been tracking the trajectory of AI/ML in drug development is well-aware of its multifaceted applications – they are as expansive as they are groundbreaking. However, with great innovation comes the critical need for clear regulation. The FDA aims to build a robust knowledge base and develop a clear understanding of the opportunities and challenges associated with employing AI/ML in drug development. Learning while regulating.

This document highlighted three critical areas:

Human-led Governance, Accountability, and Transparency: This area underscores the critical role of human supervision throughout AI/ML’s development and usage phases. It stresses the need for consistent adherence to legal and ethical standards. Governance and accountability are paramount throughout every stage of the AI/ML lifecycle, with a strategic focus on identifying and addressing potential risks. While the specific details regarding transparency, its challenges, advantages, and best practices for human participation in drug development are still under definition, continued discussions and case studies are anticipated to provide clarity.

Quality, Reliability, and Representativeness of Data: The intricacy of training and validating AI/ML models calls for thorough attention to factors like biases, data integrity, privacy, provenance, relevance, replicability, and representativeness. This is a pivotal issue in all AI/ML models, and is especially particularly important when used in highly sensitive areas such as healthcare and drug development.

Model Development, Performance, Monitoring, and Validation: This section highlights the critical nature of comprehensive documentation, maintaining a clear data chain of custody, and following established steps for model assessment. Continuous monitoring and thorough documentation are underscored as vital elements in guaranteeing the AI/ML models’ reliability and consistency over time. Real-world case studies and feedback are identified as key resources for refining model oversight and continuously validating outputs.

Although embryonic, the FDA’s proposed framework illuminates the agency’s approach towards integrating AI/ML in drug development. A fascinating revelation emerges – the same rigorous methodology the FDA has developed and refined since being founded in 1906 for drug evaluation and approval, may very well be a model for AL/ML evaluation, approval, and oversight in drug development and other high-risk applications outside of medicine and healthcare, worldwide.

To put it succinctly, the rigorous standards the FDA employs for drug evaluation could very well set the benchmark for assessing the broader applications of AI/ML, especially in high-risk sectors. A case in point? The intricate web of informed consent in healthcare. Questions like, “How does AI factor into my treatment?”, “How will medical AI leverage my data?”, and “What’s the level of transparency in training this medical AI tool?” are not just specific to healthcare but resonate deeply with AI’s broader applications. These inquiries, while intricate, are fundamental in ensuring that all AI integrates seamlessly, transparently, and ethically into our lives.

Three Possible Future US Scenarios

A New AI Regulatory Agency?

In the discussion surrounding the passage of the EU AI Act and the stratospheric AI ‘hype curve’, there emerged a call for a new single US AI Regulatory Agency. Echoing the full-scale war between the chat vs search behemoths is a skirmish on creating a new dedicated agency. On one side Sam Altman has called for a new AI regulatory Agency (accompanying hiss call for more regulation). This position was echoed by Microsoft. On the other side of the battlefield is Google who is happy with the existing structure and more self-regulation.

A critique of these positions would suggest they are each positioning where they think they can exert the greatest influence or regulatory capture. On the other hand, it is also true that the tech industry is smarting from the social media regulatory chaos and some may well welcome a one-stop-shop over having to deal with a dozen agencies. Suffice to say if it is hard enough to pass an omnibus regulatory act in the US, it is probably harder and unlikely that there is the legislative support for a completely new agency, but it remains a theoretical possibility.

Presidential Executive Order – A Strategic Compromise?

While it could take some time before the US adopts a regulatory omnibus similar to the EU, there are issues that suggest quicker action is important and attractive. And one way to get this would be through a presidential executive order. It couldn’t force all business under the tent, but it could compel all the government agencies that regulate some aspect of AI to align the processes AND it could force any government contracts to follow that rule. This is fairly compelling that many of the AI mega-corps are big government contractors.

What makes this attractive?

- With the flurry around the AI letter and the wave of AI startups there is a highly visible public spotlight on AI safety.

- If the US doesn’t act at a national level then there will be more potentially conflicting state and local regulations which could hinder critical AI innovation.

One way of providing broad based national guidance is a proposal that the President could implement the bulk of the Blueprint for an AI Bill of Rights and the NIST AI Risk Management Framework through executive order.

This would provide immediate ‘regulation’ in four ways.

- First, it could require all government agencies developing, using, or deploying AI systems that affect people’s lives and livelihoods to ensure that these systems comply with best practices.

- Second, it could instruct any federal agency procuring an AI system that has the potential to “meaningfully impact [our] rights, opportunities, or access to critical resources or services” to require that the system comply with these practices and that vendors provide evidence of this compliance.

- Third, the executive order could demand that anyone taking federal dollars (including state and local entities) ensure that the AI systems they use comply with these practices.

- Finally, this executive order could direct agencies with regulatory authority to update and expand their rulemaking to processes within their jurisdiction that include AI. (This includes, for example, the regulation of medical AI by the FDA.)

The Brookings Critical Algorithmic Systems Classification (CASC)

Short of creating a new agency, the Brookings Institution has recommended giving existing regulatory agencies two new powers. To address this challenge, this paper proposes granting two new authorities for key regulatory agencies: administrative subpoena authority for algorithmic investigations, and rulemaking authority for especially impactful algorithms within federal agencies’ existing regulatory purview. This approach requires the creation of a new regulatory instrument, introduced here as the Critical Algorithmic Systems Classification, or CASC. The CASC enables a comprehensive approach to developing application-specific rules for algorithmic systems and, in doing so, maintains longstanding consumer and civil rights protections without necessitating a parallel oversight regime for algorithmic systems.” It’s a model that focuses on algorithm regulation and combines a risk model focus with process improvements.

Future Scenarios in Sum

While it seems unlikely that a new agency would be created just to deal with AI, especially given that so many of the applications fall explicitly within the purview and charter of existing agencies, it might be possible that a special regulatory body would be created for high risk applications or those that are currently prohibited under the EU AI Act. It certainly does seem possible that a US Executive Order would be useful in aligning government agencies around the NIST Framework. Yes some process improvements, such as subpoena authority for algorithmic investigations might become attractive and regulatory agencies try to fathom the complexities of AI models and applications. Like the Red Queen’s advice – you have to be prepared to keep moving to keep up.

AI Regulation is Also About Fostering Innovation – UK +

Regulating AI isn’t just about restricting high risk uses, or ensuring that the regulations don’t limit innovation, but also, giving the importance of technical innovation to country’s economies, an emerging goal of AI ‘regulation’ is to ensure that it actively fosters and encourages innovation. For example, in 2021, the National Artificial Intelligence Initiative was launched to ensure US leadership in the responsible development and deployment of trustworthy AI . More recently the UK has embarked on an AI regulation model that emphasizes its national competitive position in AI technology (in comparison with the EU), adopting UK’s National AI Strategy, in line with the principles set out in the UK Plan for Digital Regulation. The stated strategy is that the framework will be “pro-innovation, proportionate, trustworthy, adaptable, clear and collaborative”, suggesting in some ways the UK would be an AI regulatory island apart from the EU. However, UK AI businesses would of course have to comply with the implementations of the EU Act to do business in the EU.

This focus on competitive innovation is echoed in some way in almost all of the national strategy elements of AI regulatory proposals.

- The EU AI ACT includes specific measures to support innovation, such as AI regulatory sandboxes to support Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises (‘SMEs’) and start-ups. There are attempts in the Act to create a balance in the burden across the AI supply chain, e.g., placing the larger burden on AI product manufacturers and less on the intermediate and end users. ??

- In 2023, the US The National Science Foundation published a paper: Strengthening and Democratizing the U.S. Artificial Intelligence Innovation Ecosystem: An Implementation Plan for a National Artificial Intelligence Research Resource, which provides computational, data, testbed, and software resources to AI researchers.

We want to be protected from AI abuses and guaranteed trustworthiness, but we also want the benefits of AI to not be blocked by regulation.

Some Outstanding Issues

Regulation of GPAI – the Who to Regulate Problem

The ACT includes specific measures to support innovation, such as AI regulatory sandboxes to support Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises (SMEs) and start-ups. There are attempts in the Act to create a balance in the burden across the AI supply chain, placing the larger burden on AI product manufacturers and less on the intermediate and end users. But there remains significant controversy on the regulatory focus of the Act on general purpose AI (GPAI) tools and Open-Source applications.

The purveyors of General Purpose AI, for example, ChatGPT argue that it by itself isn’t a high-risk application and so should be exempt from regulation. And this is the case that OpenAI made to the EU in their September 2022 whitepaper, titled OpenAI Whitepaper on the European Union’s Artificial Intelligence Act. The ‘opposition’ argues that this leaves it too easy to use ChatGPT or other GPAI tools in high-risk applications. Who then is responsible? In the EU act philosophy, it would be the manufacturer of the technology (who is best placed to regulate), not the end user (like the driver of a car is not responsible for the safety of its design). As in the answer to so many of the issues, a hybrid strategy likely emerges. One that combines both the risk, process, and outcomes models, and the focus on manufacturers vs. users.

Regulation of Open Source AI – the Racist “Franken-Tay” Problem

Everybody remembers Tay, Microsoft’s Twitter bot, that went quickly from friendly bot to racist rogue and had to be shutdown 16 hours from launch. Current generative AI, like ChatGPT, implements algorithmic ethical safeguards and filters to limit these issues in training, and prevent expressing these behaviors in operation. What did the Internet do? It responded with DAN ‘Do Anything Now,’ a technique to use prompt engineering to ‘jailbreak’ the safeguards built into ChatGPT. Then OpenAI continually refines its safeguards. This “arms-race” is manageable in controlled environments, but what about open-source AI?

Risk Model-based AI regulation focuses on ‘big tech’ entities like Microsoft or Google for oversight. But how do we police careless or rogue open-source developers, particularly on the dark web, from masterminding a Franken-Tay that has no guardrails? Open-source AI is a challenge. Regulatory responses include sandboxes for experimental projects, variable definitions of the ‘agent’ being regulated, and even open-source databases of algorithmic risks to promote better open-source. Still, his remains one of the big challenges in AI regulation.

The ‘Alignment’ Problem

Isaac Asimov proposed three laws to insure that ‘robots’ don’t harm humans. But how? There is a risk of ‘misspecification’ where you tell the algorithm to do, or not do ‘X’, but then it cleverly subverts the intended rules in unforeseen ways; this is called emergence. The field of AI alignment, inspired in part by Nick Bostrom’s speculations on AI controllability, seeks to meticulously synchronize AI behaviors with human intentions, serving as a pivotal domain in AI governance.

The is the core technical battlescape in algorithmic AI governance. The research delves into advanced technical methodologies like Inverse Reinforcement Learning (IRL), Supervised Learning from Human Feedback (SLHF), and Adversarial Training, aiming to mold AI’s actions to align closely with human goals. And virtually all of the AI giants have their programs to actualize AI alignment; for instance, DeepMind is pioneering ‘Safe Reinforcement Learning’, and OpenAI is advancing ‘Clarification and Reward Modeling’ as part of their ‘superalignment’ project.

This research importantly addresses both the issues of AI ethics and AI regulation. However, it does face criticism, ranging from its association with ‘longtermists’, to the inherent technical challenges in instilling alignment in systems like LLMs, MLLMs and other Machine Learning models, where the technical architecture often compromises transparency and accountability.

AI alignment is integral to the broader strategy of AI governance, but it isn’t a standalone solution. It’s a technical complement to strategies like self-governance and risk-model frameworks, hopefully yielding a harmonious governance ecosystem. The key technical challenge is how to integrate alignment and transparency.

Summary

Alright, let’s cut through the fog: Feeling a smidge safer? Yes, but clarity’s still a luxury. We’re doing better than our previous challenges of facing internet / social media exploitation and risks. Thanks to the power players—AI titans, policy wonks, and ivory-tower scholars, rolling up their sleeves and crafting the AI rulebook, we’re steering away from the dark abyss of unchecked digital chaos.

However, there remain tactical glitches in the matrix: The EU’s act awaits ‘implementation’, is the risk-based model cutting it? Jury’s out. Transborder tech drama? The US… and incomplete beginning. This all necessitates a whole next level of harmonization.

And there’s still the strategic Red Queen dilemma. With the AI sphere and its numerous applications evolving rapidly, three pivotal concerns arise:

- Can the rule-makers even keep pace with this relentless tech evolution?

- How adeptly can developers navigate this shifting regulatory terrain?

- And the million-dollar question for all players—what’s my responsibility?

It’s encouraging there’s no single echo chamber amongst Big Tech – for example, the new single-agency concept is supported by some and opposed by others. Some cheer on new regs, while others play defense. This diversity can help, but staying vigilant is even more so a necessity.

What about the Terminator? Most of the chatter’s about benign, commercial bots. But let’s not kid ourselves: some tech is weaponized, ready for cross-border mind games and kill missions. The big military players flex both offensive and defensive muscles. But those second-tier nations? Vulnerable. And a few could be existential bad actors. Notably, Pippa Malmgren, former US and UK cabinet advisor, argues that we’re already entrenched in a technological World War III.

To highlight where we stand consider… US Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer convened a private session on AI regulation with 60 senators and the key tech heavyweights. ‘X’ Chairman Elon Musk emerged saying there was “overwhelming consensus” for regulation on AI… And Lawmakers said “there was universal agreement about the need for government regulation of AI, but it was unclear how long it might take and how it would look”.

So, whether you’re coding, legislating, or just consuming AI, get focused. Assign a watchdog for this circus because you don’t want to be the last to know.

Stay tuned for our part three of this series, where we examine the impact of AI Ethics and Regulation on Business & Investment Strategy.